How we practice Architecture.

At its most fundamental architecture has two concerns: the material (what it looks and feels like) and the social (the activities it encourages). At TOLO we aim to find interesting and original ways to address both concerns.

The material qualities of a building connect it to a larger conceptual idea, to the site, and to its cultural and historical context. For example, the architect Louis Kahn is associated with the idea of “truth in material” meaning that a material was supposed to represent the work it was doing. Kahn suggested to his students that they should ask their materials for advice: "You say to a brick, 'What do you want, brick?' And brick says to you, 'I like an arch.' And you say to brick, 'Look, I want one, too, but arches are expensive and I can use a concrete lintel.' And then you say: 'What do you think of that, brick?' Brick says: 'I like an arch.'" For Kahn, bricks should work in compression, meaning they are used to support the force exerted on the building by gravity. On the other hand, a material such as wallpaper would be used as a surface treatment to “decorate” the interior of a building. Post-modernism upended this direct connection between a material and its function. In the work of Frank Gehry, for example, chain-link fence (a material previously only used to demarcate a property) was used in his house as cladding. The use of a lowly material like chain link, not only represented the punk aesthetic that Gehry became known for, it was also used as a political tool to oppose what Gehry referred to as “the smugness of the middle-class neighborhood.” The rejection of “truth in materials” by architects like Gehry gave license to others to use materials in a way that is contrary to expectations.

Our work at TOLO navigates between these differing ideologies. We tend to assign a particular "meaning" (as troublesome as this word is) to a material, such as using copper shingles as a wrapper. But we also understand that the role that a material plays is mutable. A material can act differently in different settings. For us though, it is important that the material exhibits intention. That its use in a particular project connects to a larger strategy be it technical, sensorial, or narrative. The material strategy that we choose to employ in a given project is influenced by three things: 1) precedent (a work of art or architecture that came before), 2) the site (the urban or natural context it is being placed into), and 3) the formal or spatial strategy (how the material is located to help explain the shape or organization of the building). Perhaps the best way to explain the role that material plays in our practice is to describe three examples that illustrate our approach.

1. The use of tilt-up concrete in Saladang Song – The precedents for this project come from both high and low culture. At the high end is R.M. Schindler’s own Kings Road House in West Hollywood. Schindler cast the tilt-up concrete panels on site and placed narrow translucent glass panes between the panels to further emphasize the tectonic/material strategy. Meaning the panels were doing all the structural work so the glass in between could focus on bringing in light. Likewise, in Saladang Song the tilt-up concrete allows the screens in between to be both decorative and to bring in light. On the low end our precedents are “cheap and fast” tilt-up warehouses and big-box stores common throughout Southern California. The restaurant’s small budget along with a desire for privacy and a large open space gave us the idea to use this unexpected construction strategy.

Saladang Song, Pasadena, CA designed and built by Peter Tolkin.

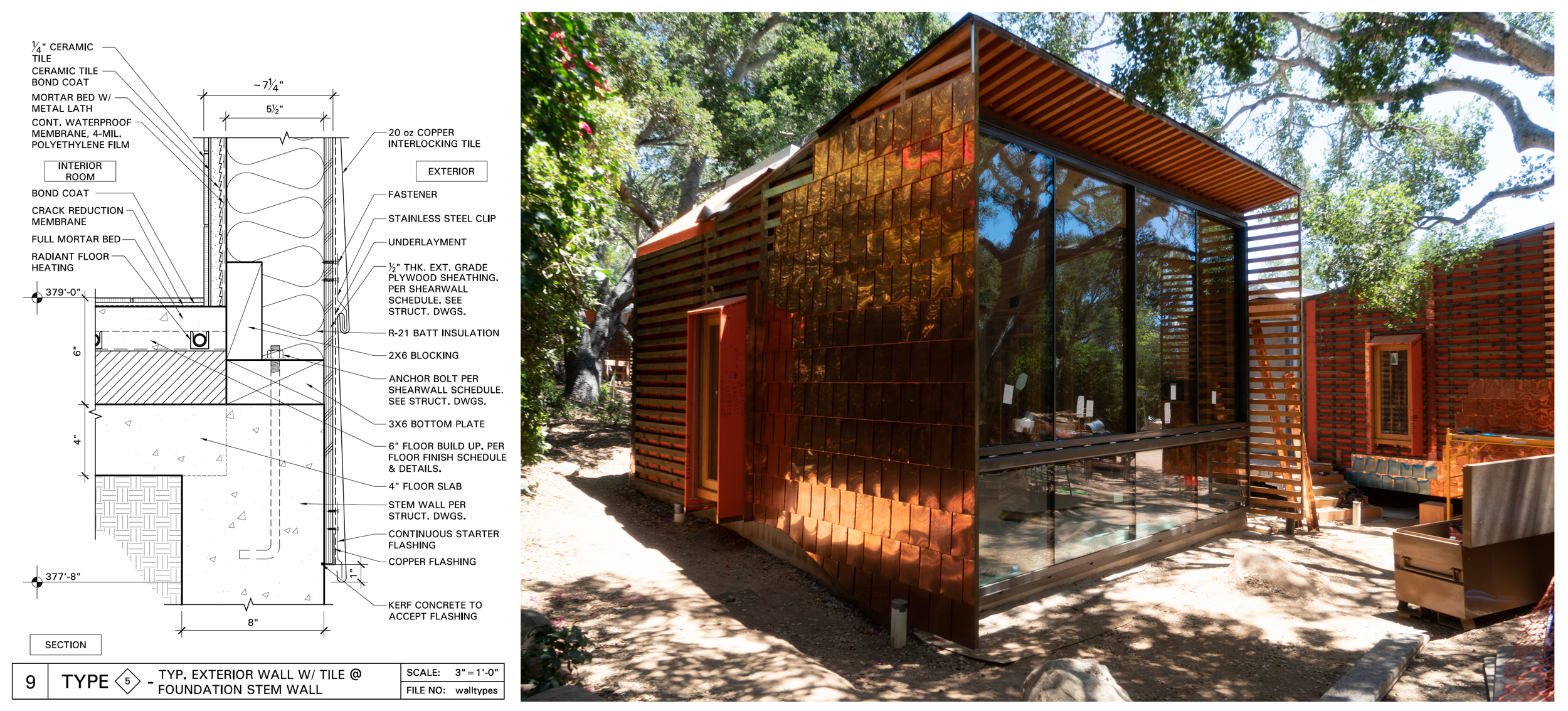

2. The use of copper shingles at the Branch House – The primary objective for the Branch House was to design a house that felt “of the place.” This was done by siting the house within the park-like setting of the native shrubs and oaks, and by specifying a copper shingle skin that would develop a verdigris patina as it aged. The green and copper cladding not only protects the house from fire, the changing color of the tiles plays a key role in visually connecting the house to its natural surroundings.

Branch House in Montecito, CA. Drawing of the rainscreen detail and photograph of the copper (before it developed patina) under construction.

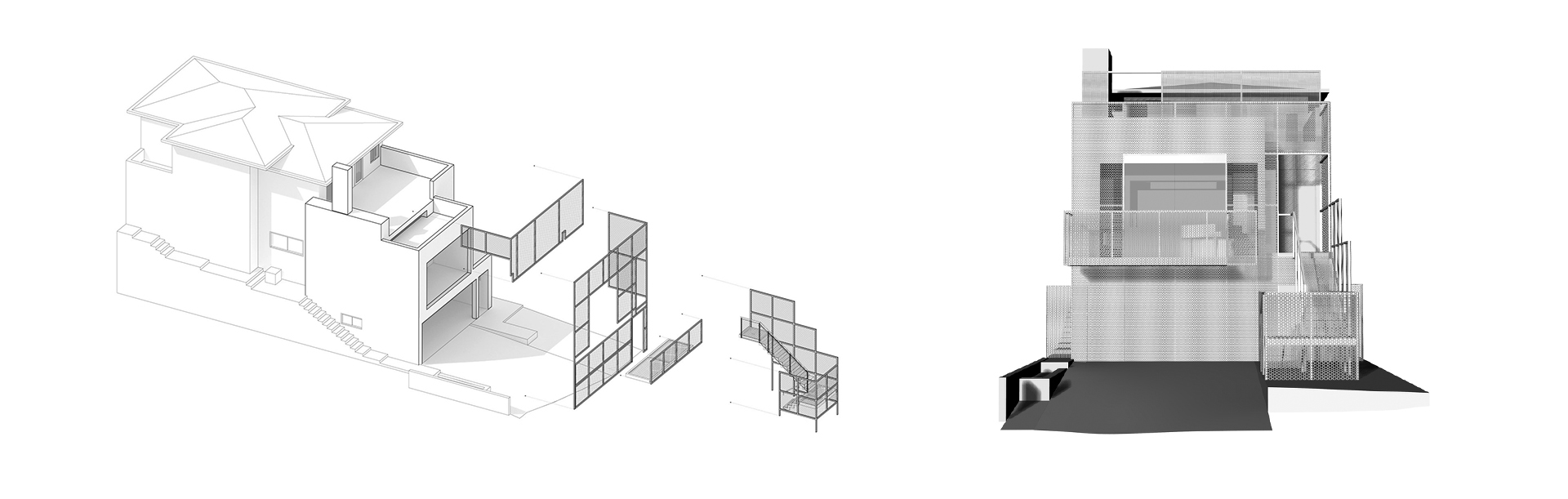

3. The use of gridded, perforated metal screens at the Gaines Landaverde Residence – The design strategy for the project was to expand the house and add a perforated metal screen façade at the front. The material choice for the cladding made sense to us given our interest in loosely referencing the grids that the artist employs in his own work. The semi-translucent quality and varying grids of the perforated panels mediate the landscape outside or the inhabitants and also reconfigure the activities happening within the house for those peering in from the outside. This strategy also makes clear that the façade is an addition since the character of the original character of the house is still allowed to bleed through.

Drawings of the Gaines Landaverde Residence renovation and addition.

Our concern for the social aspects of architecture is also central to our architecture. As we design we continuously look for ways to activate a space, making it relevant and useful to the people that use it. The decision on how to best activate a particular environment is made through conversations with the client. When asked to design a house, we often begin the design process by asking our client(s) to fill out an extensive survey. The survey addresses issues of lifestyle, such as how a person lives, works, and entertains. “Do you like to spend time in bed other than when you’re sleeping?” might seem a bit too personal, but it helps us understand a person’s behavior in the most private of spaces. Other questions gather information about the kinds of things people collect, whether they like to garden, or how many guests might be invited to a Sunday barbeque. For larger commercial or multi-family projects the questions may be less specific to a family’s distinct choices, but they are still designed to give us a clear idea of the people that will be using the space.

The social aspects of architecture don’t only involve the user, they also involve the larger society. It may sound like a grand pronouncement, but we strongly support the idea that architecture should be engaged in the betterment of society regardless of the scale of the project. All types of issues influence this larger goal – economics, regulations, norms, sustainability, and the cultural milieu the project sits within. A project, even a single-family house, can play a role in improving people’s lives. On economics, we are always looking for ways to be smart about how we build, avoiding waste and finding creative (and sometimes unusual ways) to build less expensively. On regulation, it is important to us to be respectful of the regulatory requirements that impact human health and wellbeing, being cognizant that laws, like everything else in life, are fallible. For example, the enactment of the Americans with Disability act made it possible for millions of people with mobility issues to navigate the built environment. California’s Title 24 rules established strict guidelines to minimize energy consumption to help the environment. Affordable housing legislation has helped preserve and add homes for low income families. Of course, when bad legislation is enacted that discriminates against people instead of helping them we make a point to be voice our opposition (see our XYYXXY Accessible Restroom project and its accompanying story "Questioning the rules and social mores that are built into the design of bathrooms"). On norms, we are interested in how people think the world should look and behave; taking this as an opportunity to question these beliefs. In seeking to understand if these beliefs are fixed or malleable we can develop unconventional designs that are also sensitive to people’s notions and opinions. On sustainability, we believe that designing sustainably is as much about tapping into the experiential qualities of place as it is about being energy efficient. On addressing the cultural milieu, we are all of course products of our culture. It is important that our designs be reflective of the time and place in which they exist. In our work we might reference a past work of architecture, or borrow a textile pattern from another place, but we strive to synthesize these influences to create something original and current. As with the explanation above on the role that material plays in our work, we will once again use three examples to illustrate the role the social plays in our work.

1. Encouraging play with inflatable architecture – Made of dunnage bags, the giant, inflatable versions of packing peanuts used to secure heavyweight cargo in containerships, this piece has been installed at a variety of arts and music festivals. It is cousin to the inflatable castles seen at children’s birthday parties and the pneumatic architecture of the late1960’s and 1970’s utopian counterculture movements. One example are the inflatables by the collaborative Ant Farm, which were created to provide a non-hierarchical space where people could freely interact with one another (see http://inflatocookbook.kadist.org/). Similarly, the Dunnage Ball, in all of its incarnations, encourages participation and uninhibited play in young and old alike. No doubt that there is social good in the pleasurable effects of excitement and optimism associated with this kind of play.

Dunnage Ball at the Santa Monica Glow Festival. Photographs by Joshua White.

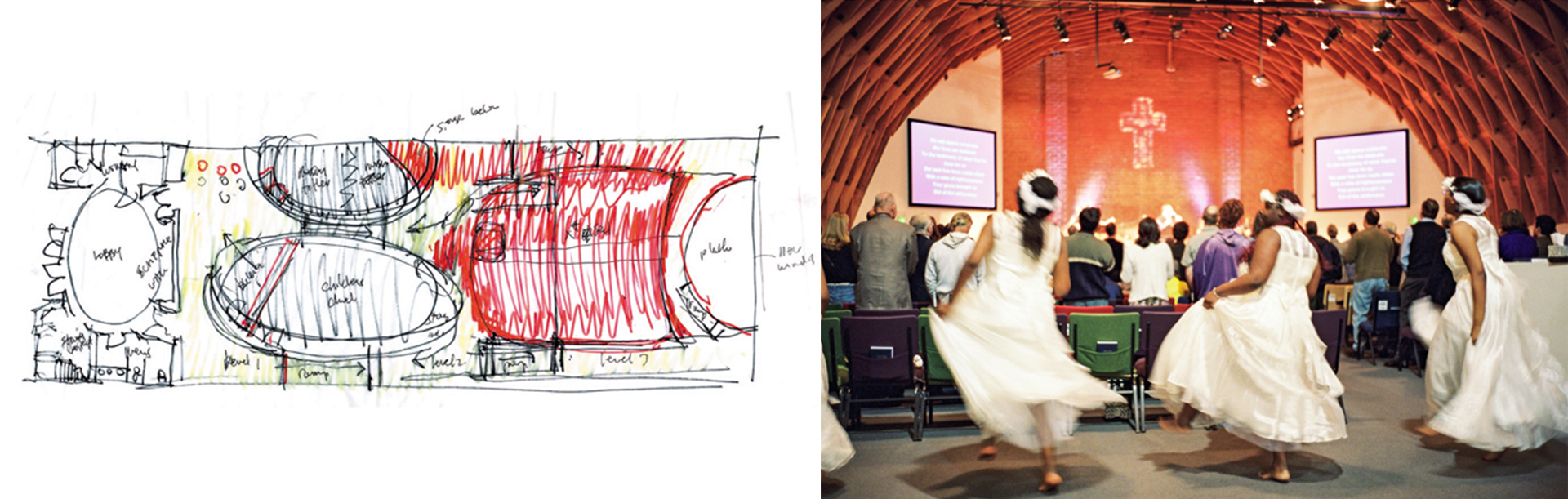

2. Turning an art house movie theater into a space of worship for a Pentecostal congregation – The pastor for this congregation asked us to reconfigure the old theater to accommodate a sanctuary space for 300 adults, a smaller worship space for children, and a still smaller space for infants and toddlers. We proposed adding two shell-like volumes into the existing space that related to the existing Lamella roof structure. Instead of the regular triangular geometry of geodesic domes developed by Buckminster Fuller, we proposed using a more irregular geometry. We developed a notational system, developed in collaboration with our structural engineer Karl Blette, that would allow for flexibility in the geometries of the shells based on local variation that accounted for the “rough” framing process. This improvisational system allowed for a design that could be modulated on site by the contractor. Pentecostal services are known for their ecstatic and performative qualities, filled with preaching, personal testimonials, and faith healing. This project drew a connection between the social aspects of our clients’ religious practices and the methods we used for its design and construction. Peter termed this as “less static, more ecstatic.”

Sketch showing the insertion of two additional volumes into the old theater. Pentecostal dancers during a service. Photo by Peter Tolkin.

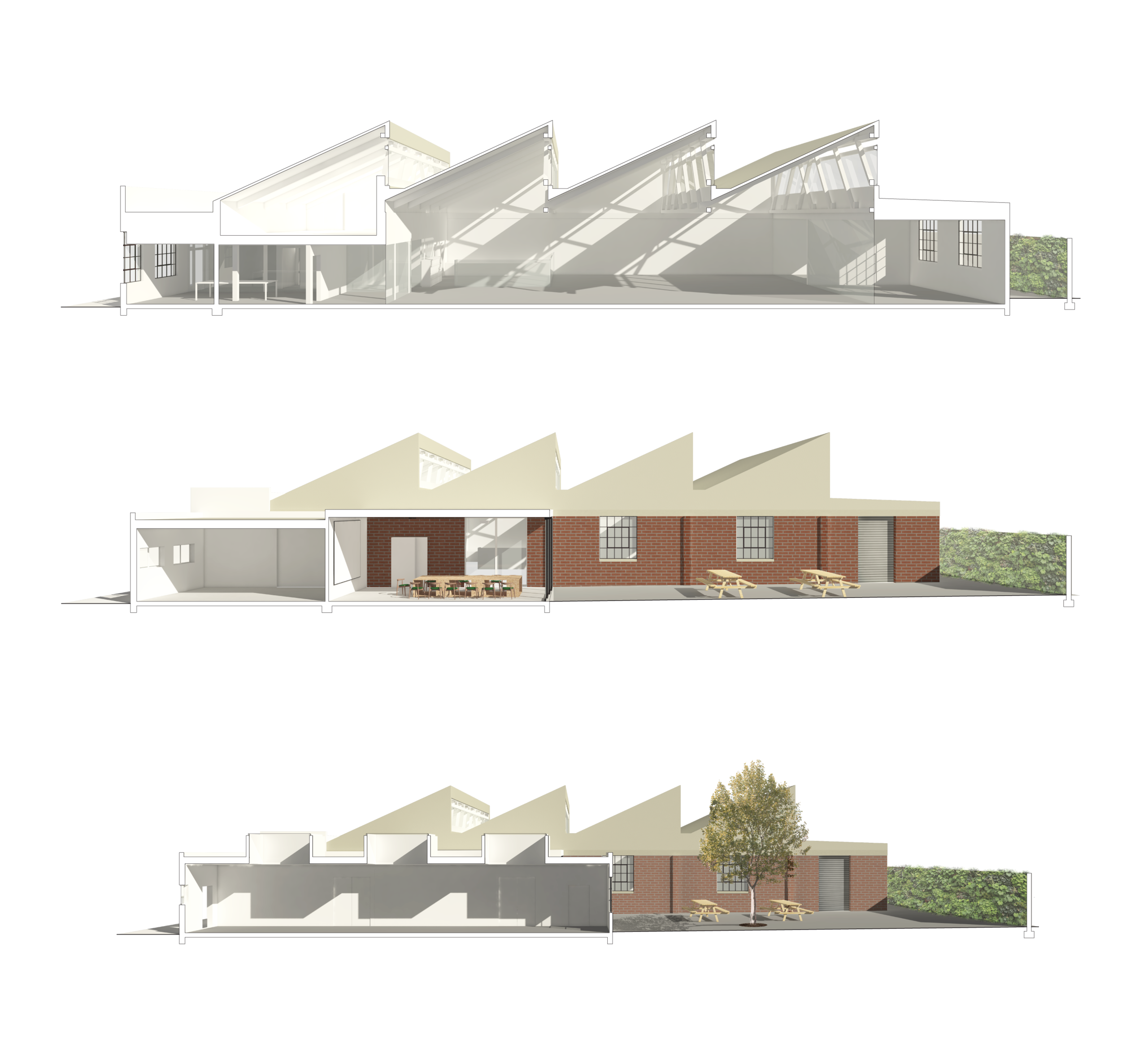

3. Adapting a saw-tooth roof warehouse in Huntington Park into a creative arts space – Like the Pentecostal project, this too is an adaptive reuse project. In this case we were asked to convert a light industrial manufacturing building into an arts complex to accommodate artist Charles Gaines' production space including a clean room for drawings, offices and social spaces for his staff, a conference space, a gallery, art storage, and a personal space for him away from production. Adaptive reuse of older buildings (turning something that was designed for one use into a different use) is a powerful sustainable alternative to building new and to the demolition of existing buildings. It takes advantage of the remaining life of a building, conserving the embedded energy of the building’s materials and assemblies. The choice to maintain and reuse versus rebuild is not without complications. Re-use requires significant work to precisely document what’s existing and flexibility in addressing issues that come up during construction, such as those hidden behind walls that must be moved or repaired. Being creative in how we adaptively reuse buildings in an era of climate change is central to our ambition to design buildings that look good and that contribute to the public good.

Other interviews about our design process:

Work

Office

Work

Office