Backyard Bungalow, Los Angeles, California

It is undisputed that housing in Los Angeles is unaffordable and unequitable. Progress is slowly being made to increase the availability of affordable homes by building high-density housing along transit corridors and in downtown areas. Still, much of Los Angeles is made up of single-family neighborhoods, where high-density housing typologies would be disruptive. Though frequently vilified by progressive planners and architects, many of us still aspire to own a single-family suburban home. Who could fault a person’s desire for privacy and open space? The failings of single-family houses are that they are land and energy intensive and thus diametric to affordability, public transit, and minimizing our carbon footprint. Allowing for greater density, in a way that is sensitive to the scale and qualities of suburbia, is one way to mitigate these downsides.

Our entry (and the premise of the competition) shows that with minimal zoning changes, Los Angeles can densify the suburbs and maintain the coherence and stability of its neighborhoods. In addressing the prompt to create housing that is suited to this city, we felt that two related characteristics distinguish Los Angeles from other localities: our mild weather and our legacy of indoor-outdoor living. The city has a number of legendary housing examples that take advantage of this, such as the multi-unit Neutra VDL House and Schindler’s Kings Road House (both now house museums), the courtyard housing Villa Primavera (the setting for the film noir “In a Lonely Place”), and St. Andrews Bungalow Court.

Mid-density bungalow courts are particularly relevant case-studies when considering ways to transform L.A.’s single family lots, both because of their architecture and their social benefit. The small size of the units makes them more affordable and the complex’s scale and layout allows it to easily co-exist alongside single-family housing. As we began to tackle this design challenge, we interviewed a number of young renters, ages 25-35, asking what they liked and disliked about their current living situation. All of them wished they had access to more private outdoor spaces, even those that live at a bungalow court. They explained that while the shared central court provides greenery and space to be outside, they didn’t feel like they could use this space for BBQs, for their children to play, for them to garden, or to feel at ease taking a nap outdoors.

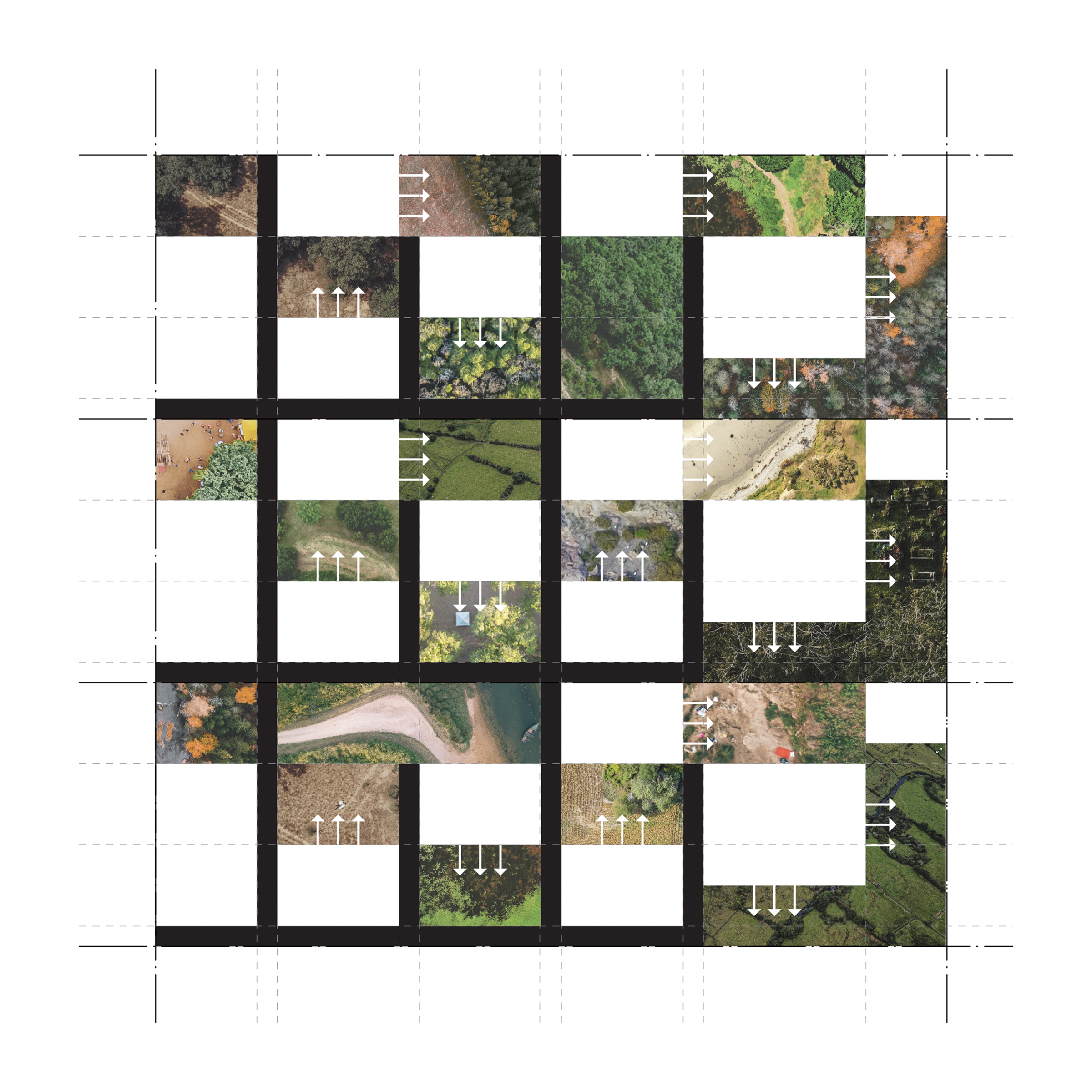

Site strategy over multiple lots. White arrows represent relationship of unit to their “back yard.”

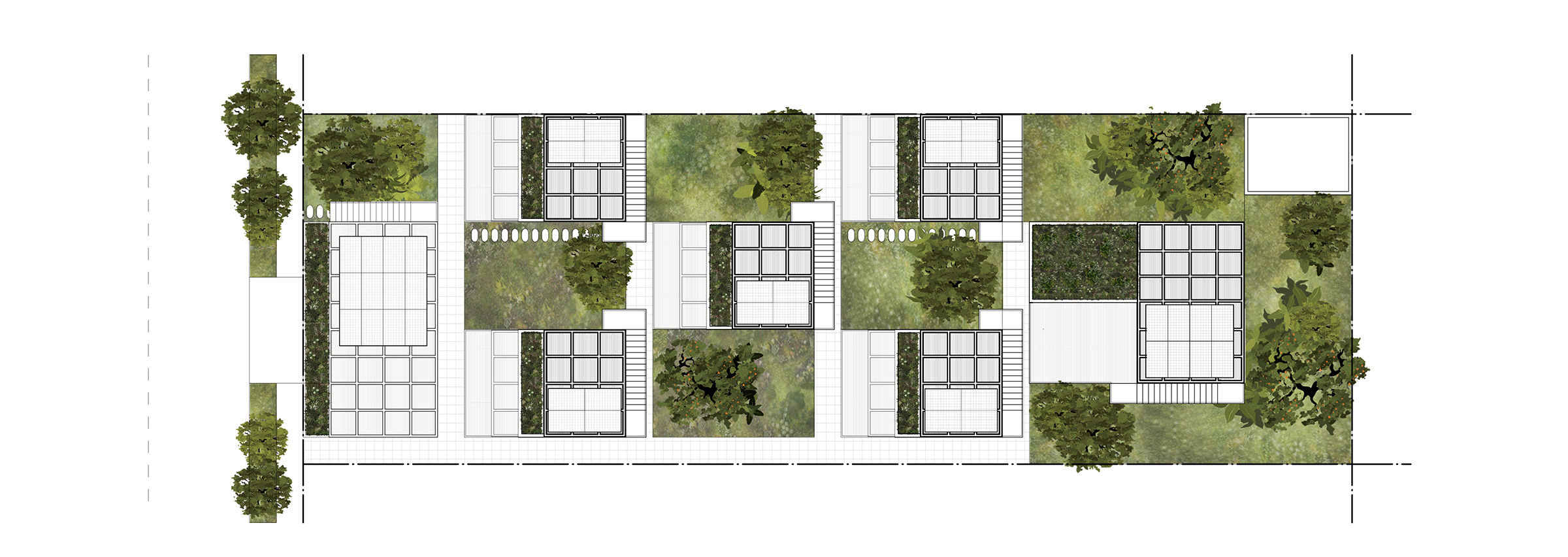

Our proposal is a hybrid of the bungalow court and the single-family suburban home. As with the bungalow court this project is made up of detached units, but it swaps the typology’s communal court for a suburban model of individual backyards, balconies and terraces. Our plan also re-orients the detached units to allow for greater privacy within each home. The front yard, the symbolic and most unused element of the single-family suburban home, was eliminated. This project brings down the cost of housing by building small, increasing density, and through the use of modular construction methods. The units are designed to maximize opportunities to extend the living spaces outdoors. Each unit has their own back yard and screened views into their neighbor’s yard. Each unit’s second floor balcony is large enough to be used as a workspace and the roof terrace is designed to accommodate a vegetable garden and deck. Above the roof deck, a trellis accommodates four to eight solar panels/small unit (sixteen panels on the larger unit). Space above the garage can be used for shared activities.

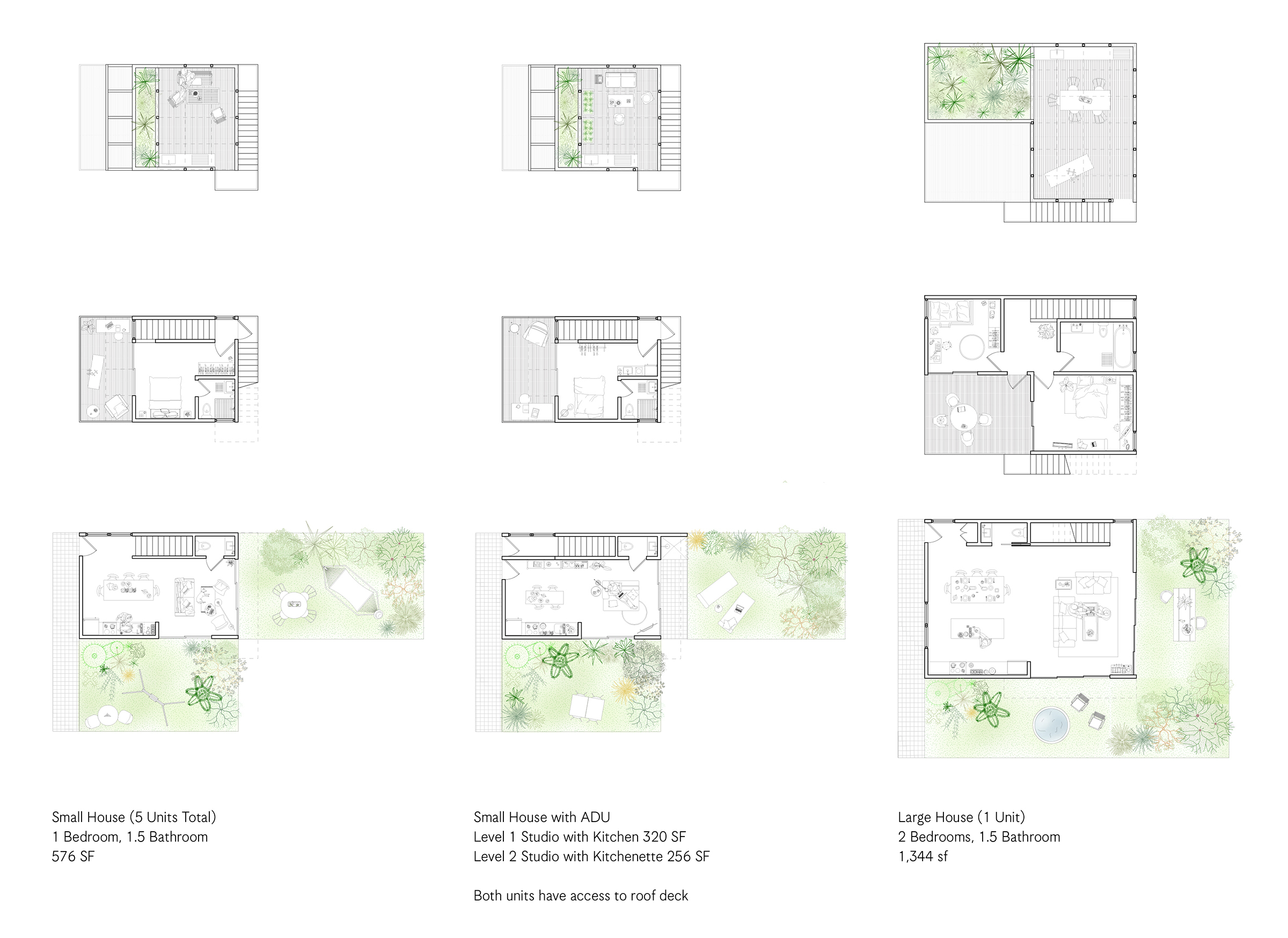

Our site organization allows for a total of six units – five 1-bedroom and 1.5-bath units of 576sf each and one 2-bedroom unit of 1,344 sf, for a total buildout of 4,213 sf. Each of the smaller units also have a private 384 sf back yard, an 128 sf balcony, and a 288 sf roof deck. The large unit has a 1200 sf yard, a 192 sf balcony, and a 576 sf roof terrace. In effect the small units each get 800 sf of exterior living space and the large unit gets almost 2,000 sf. The site strategy also allows for fewer units to be built, with any unbuilt area used as common recreation space.

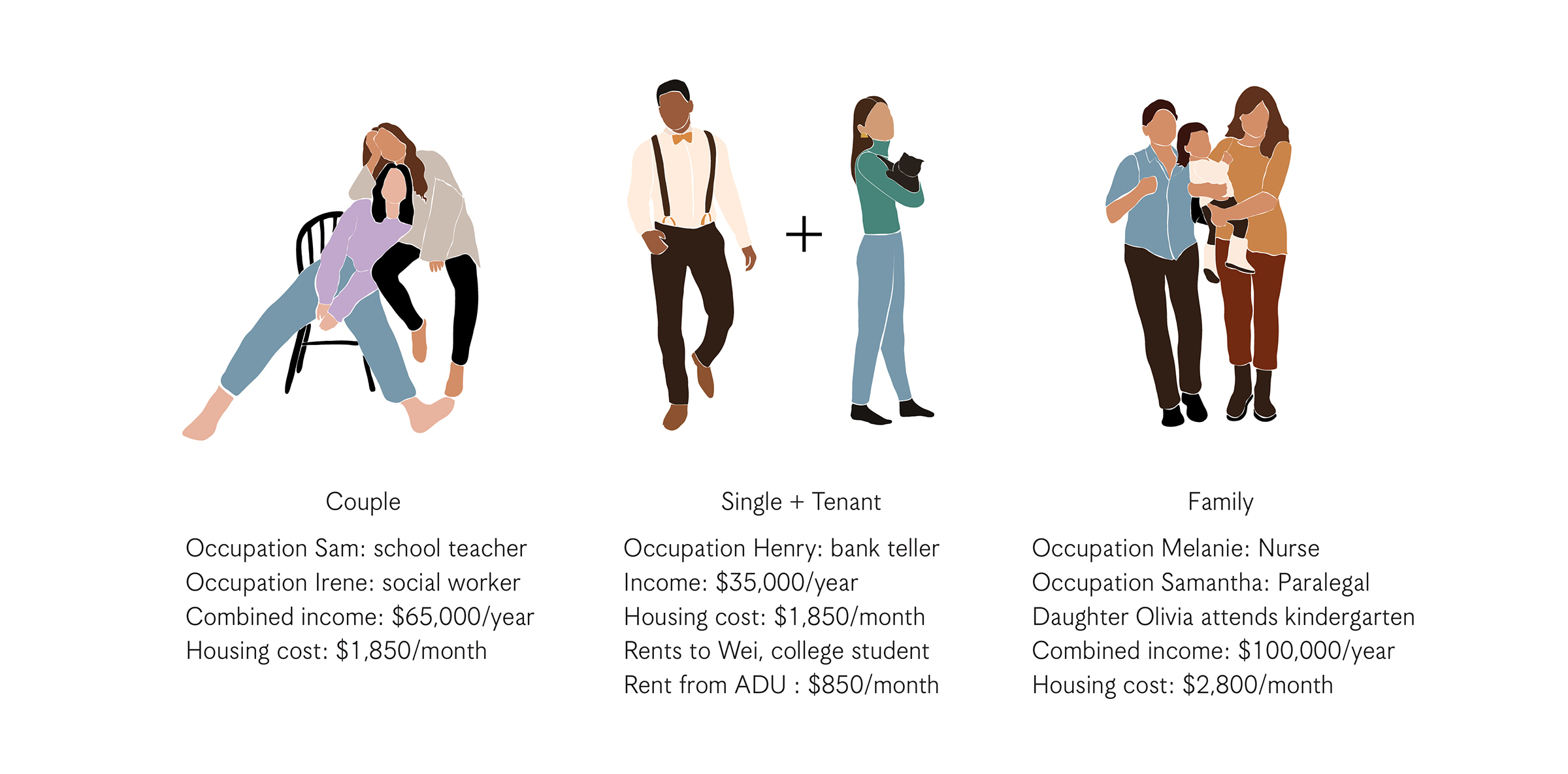

To verify the affordability of the units we ran through a variety of scenarios for three hypothetical buyers. We chose to test the project on buyers versus renters, based on the desires expressed by the young renters we interviewed, and also because home ownership is a major vehicle for building wealth and economic opportunity for low-income and minority families. Our best-case scenario, even with an aggressive construction budget, showed that even the smaller units would still be unaffordable to many. We decided to design the smaller units to be easily subdivided, allowing an individual to create a junior ADU that they could rent and maintain privacy. This design stretches what is allowed under the state’s ADU ordinance, but we believe it meets the “spirit of the law.”

To estimate costs, we found 10 vacant lots, of similar size to ours, that were for sale in North Hollywood for $2.3 million ($230,000/lot). We estimated the cost of construction at $300/sf and added in soft costs and permitting. The approximate cost for each of the smaller units was $320,000, which corresponds to $1,850/month including taxes and insurance (not including utilities), given a 5% down payment. Renting out an efficiency unit for $850/month would make the unit “affordable” to a single person making a median wage of $35,000/year (35% of their income). A couple making a combined income of $65,000/year would be able to afford the full 1-bedroom unit given current interest rates. While the 2-bedroom unit would cost approximately $480,000 ($2,800/month), which would be affordable to a couple (or roommates) making a combined income of $100,000/year.

This costing exercise further exposes the city’s affordability problem, which while improved with this denser housing strategy, would still be out of reach to many low-income families. To be truly affordable local and state governments must find ways to subsidize the cost of housing by offering loan forgiveness programs, increasing the minimum wage, supporting public healthcare, and subsidizing green energy strategies. Policy changes that allows “Backyard Bungalows” in combination with financial support may just work to give more Los Angeles residents the opportunity to own their own home.

View of kitchen in small house

Front elevation from street

Status: Unbuilt

Year: 2021

Project Team: Sarah Lorenzen, Peter Tolkin, Socrates Medina, Shirley Hsu and Ayda Abar

Part of the Low-Rise design challenge. Organized by the Office of Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti and the Chief Design Officer for the City of Los Angeles, Christopher Hawthorne

Category: Fourplex

Juror's Note "for a careful analysis of the needs of and obstacles facing younger renters in Los Angeles and arrangement of interior and exterior spaces to maximize privacy and autonomy for residents."

Work

Office

Work

Office